In the heart of Paris on the banks of the Seine is a small and pretty square – Place du Chatelet. You must have passed it if you have ever been to Paris: two elegant theaters on the sides, a graceful fountain in the centre buried in green trees in summer, crowds of passing tourists – nothing else reminds you of the fact that once upon a time the darknest and the most blood-curdling building in Paris was located here.

The Grand Châtelet: Paris’ Portal to Hell

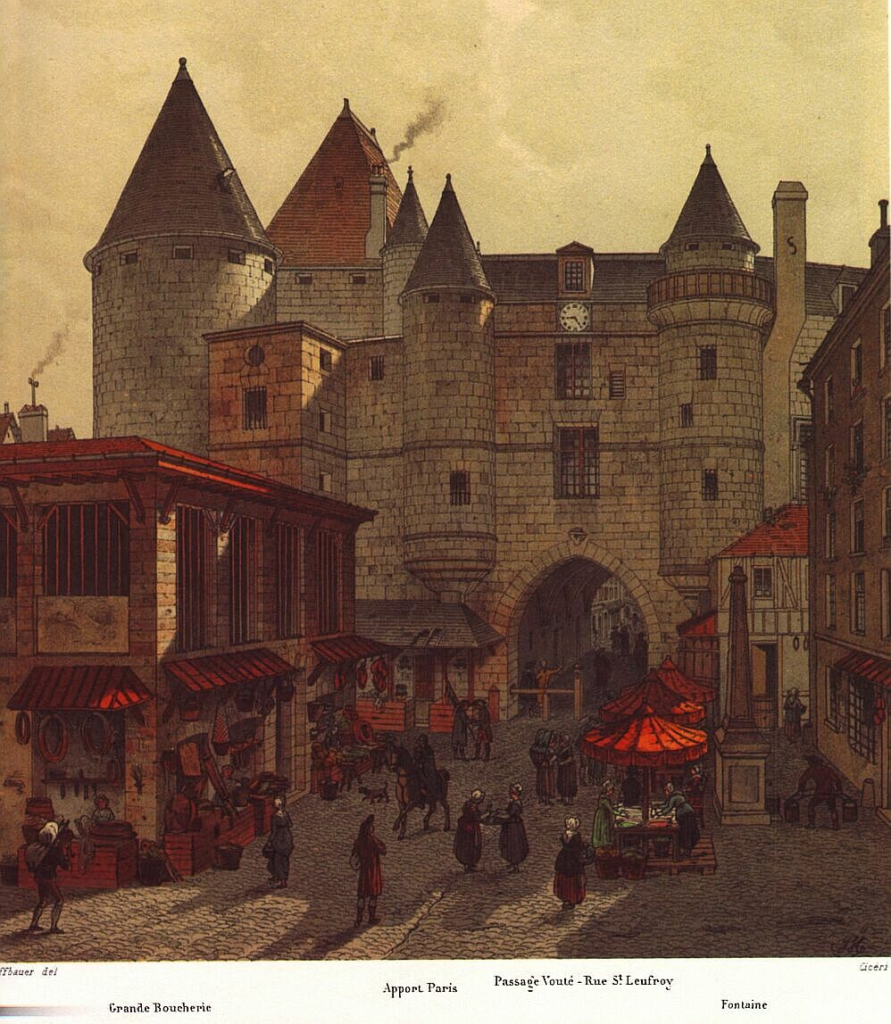

In the heart of Paris, where the bustling Place du Châtelet now stands, once loomed a fortress so sinister that its very name evoked a one-way ticket to hell. The Grand Châtelet, with its dark stone walls and imposing towers, was a testament to the city’s turbulent past and its thirst for justice, however brutal.

The Grand-Châtelet, after Gibet de Montfaucon (gallows), the most sinister building in Paris, both for its form and its purpose because of its proximity to the cesspool that has made this district one of the most foul places in the capital. Jacques Hillairet, Connaissance du vieux Paris, Éditions Princesse, 1954, pp. 83.

The area around the Châtelet reeked of the smell of drying blood from the nearby abattoirs and "the outflow of the great sewer that ran into the Seine between the Pont Notre-Dame and Pont au Change. David Garrioch, Le Making of révolutionnaire Paris, University of California Press, 2002, p. 18.

A Fortress Against Invaders

The origins of the Grand Châtelet are shrouded in mystery. Some ancient historians believed that its foundations were laid by none other than Julius Caesar, envisioning it as a massive tower to defend Lutèce.

However, this is likely a legend. The most credible record points to Charles the Bald, who in 877 AD, ordered the construction of fortresses along the Seine to shield Paris from Viking invasions. By the time of the siege of Paris in 886, these fortresses, including the Grand Châtelet, played a pivotal role in the city’s defense. As one source states, the Châtelet was “one of the four master gates of the city,” a sentinel against external threats.

A Prison of Nightmares

Over time, the Grand Châtelet evolved from a military fortress to a symbol of royal justice and power. Its dungeons became synonymous with horror. Those unfortunate enough to be imprisoned within its walls faced conditions so atrocious that death was often a mercy.

One of the most notorious cells was the “Chausse d’hypocras” or the “Fosse.” Prisoners were lowered into this watery pit with a pulley, their feet perpetually submerged. The cell offered no respite, no chance to sit or lie down. As one chilling account puts it, “The life expectancy there was fifteen days.”

The First Morgue of Paris

The term “morgue” originally referred to the act of prison guards intensely scrutinizing the faces of inmates to identify them in case of escape or recidivism. Over time, this term was used to describe the cells themselves. The Grand Châtelet housed Paris’ first morgue, a place where the city’s dead, especially those found on the streets or pulled from the Seine, were displayed for identification. As one source recounts, “The nuns from the nearby Sainte-Catherine hospital were tasked with washing these bodies and giving them a proper burial in the Cemetery of the Innocents.”

The Fall of the Grand Châtelet

Despite its significance, the Grand Châtelet was not immune to the winds of change.

By the late 18th century, there were calls to demolish this aging prison, especially given the deplorable conditions within. The Revolution accelerated its downfall.

On September 2, 1792, rioters stormed its gates, massacring prisoners believed to be hardened criminals. The fortress’s final death knell came a decade later. Demolition began in 1802, erasing this dark chapter from Paris’ landscape but not from its memory. As one source poignantly states, “Well, you know what, friends? I love our era!”

Today, as Parisians and tourists alike enjoy the lively ambiance of Place du Châtelet, few may realize the ground they walk on once echoed with the cries of the damned. The Grand Châtelet, in all its grim glory, serves as a haunting reminder of a Paris long gone, where justice and cruelty often walked hand in hand.